Online Exhibition

Welcome to the Sutton Gallery Viewing Room.

Please provide your contact information to view the current selection of works.

By sharing your details, you agree to our Privacy Policy and will receive gallery newsletters.

Nicholas Mangan Termite Economies: Neural Nodes and Root Causes

15 – 30 May 2020The following is an essay by Helen Hughes developed in conversation with Nicholas Mangan and written in response to his exhibition Termite Economies: Neural Nodes and Root Causes. In this text, Hughes exposes the metamorphosis undertaken between the three phases of Mangan’s Termite Economies series, while tracing the conceptual lineage of this body of work within his practice more broadly.

Neural Nodes and Root Causes is the second exhibition at Sutton Gallery and Sutton Projects in Nicholas Mangan’s Termite Economies series, which began in 2018. But the artist has been thinking about termites for a lot longer than this. For his Untitled (nest) (2004), Mangan altered a readymade aluminium ladder so that it dripped with long, pointy nests riddled with sponge-like holes. A number of the rungs seemed as though they had begun to be colonised by termites too—a slow-creeping takeover of the object, reminiscent of the bejewelled, half-dead/half-alive trees, alligators and birds of J.G. Ballard’s Crystal World (1966). Termites continued to appear in some of Mangan’s first major solo shows out of art school: The Colony (2005) and Mutant Message (2006). These projects featured a range of carved wooden sculptures, some of which again gave the appearance of being termite infested or indeed built by termites as opposed to a human. With these works, Mangan introduced the themes of labour, mining, extraction and destruction as key sculptural—as well as social, political and environmental—concerns that have sustained his practice to this day.

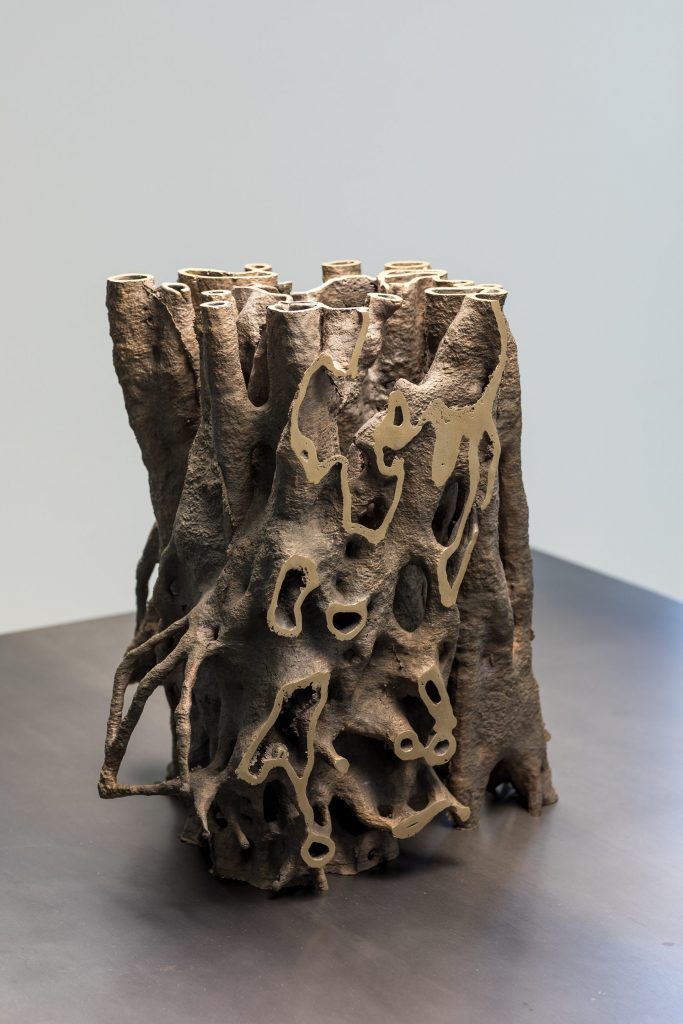

Termite Economies: Phase One pivoted on an anecdote about scientists from the CSIRO using termites to detect mineral deposits, like gold and copper. Its sculptural forms blended mining infrastructure, like quarries, with the interior tunnels of termite mounds to create a visual metonym for unmitigated human greed, colonisation and destructive resource extraction. Phase Two, Neural Nodes and Root Causes, picks up on the way software developers have utilised concepts of termite stigmergy and swarm behaviour to model neural networks in machine learning. The connotations of vast mining infrastructures in Phase One are here scaled down to the size of the human brain: termite tunnels coalesce with neural nodes.

Machine learning depends on access to huge quantities of data extracted from people simply using the internet. This data is harvested from various social media platforms, web-browsers and geolocation apps, then used by those companies and/or sold on to third parties. Not only is the data used or sold for profit, it is also deployed to reshape the entire world—through pioneering new forms of social and political control based on targeted advertising, news media, politicking, and so on. This trend has led some economists to compare data harvesting to the enclosures of common land in England and Wales over the course of the last millennium: the process of privatising property that previously belonged to no one for the profit of an elite few, while further dispossessing the poor. Where Phase One had a strong centrifugal force—in the sense that processes of colonisation and resource-extraction, like empire, tend to move outwards from a central point—Neural Nodes and Root Causes, by contrast, bears a centripetal force. Its operations move from an outside point in, colonising the interior of a chosen structure, in this case the human brain. This centripetal motion is fundamentally complex: it simultaneously connotes processes of self-exploitation (like autophagia or self-cannibalisation) and productive rewiring. The artist explains that he is interested in exploring ‘the brain as a working model [like] the underground goldmine for Termite Economies: Phase One, which was a site of activity, a place to start digging, to think about labour, consumption, digestion and spit.’1 In this project, he continues, ‘the human brain becomes the central form to ponder connectivity, collectivity, metabolic shift and as a model diagram for not only building new neural pathways but perhaps a kind of hypertrophy that reroutes or reassembles larger social systems, in which the individual human brain is just one node in a larger network.’

There is a particular violence at play in the sculptural vocabulary of Mangan’s new works: central to them is the sheer cut, cleave or cross section. The organic, vascular-like curves of the sculptures are severed at precise right angles, creating perfectly flat, cube-like sides. In bringing these two diametrically opposed vocabularies together, Mangan took his cue from scientific approaches to the study of termites. A key research document for Termite Economies is a black-and-white photograph taken in 1923 titled ‘Sawing A Termite Nest’ (Australian Museum Archive). Taken by entomologist Anthony Musgrave, it depicts two men: one is shown vertically hand sawing through a termite mound, while the other is poised behind a large tripod-mounted camera, filming the actions of his colleague. For Mangan, this image distils the destruction inherent in certain objectifying, scientific attitudes. It also articulates the ever-widening ‘rift’ that separates humans from ‘nature’ more broadly, with catastrophic implications for both. Whilst the cut ‘provides a clear view inside, exposing the material constitution of the subject,’ he explains, ‘it cuts against the material surface’ and ‘emphasises this condition of separation.’2 For this reason, the cut and cross-section have been defining methodological approaches across both his sculptural and filmic montage works over the last decade: evident, via the practice of dendrochronology, in Ancient Lights (2015) as well as the sliced ancient coral coffee table in Nauru—Notes from a cretaceous world (2010).

Untitled (nest) (detail), 2004, aluminium ladder, Western red cedar, Tasmanian oak. Art Gallery of New South Wales. Acquired 2015.

Man sawing section out of termite mound nest, 2019, digital print, 102 x 73cm (framed). Courtesy Australian Museum Archives. Photographer Anthony Musgrave.

Neural Nest (slice), 2019, 3D printed Polymethyl methacrylate and acrylic paint, 30 x 40 x 28cm

Neural Nest (slice) (2019), currently installed at Sutton Projects, is particularly evocative in its use of the cut and cross section. This sculpture is based on a neural node model of a human brain (the model provided by Monash University’s Neuroscience Department). Using generative software, tellingly called Grasshopper, Mangan plugged in an algorithm based on termite behaviour patterns in an experiment to reroute the brain’s nodes according to certain termite behavioural tropes—like those of stigmergy and swarm. In effect, he modelled a cross-species, Frankensteinian patchwork of human brain and insect logic. The neighbouring collages at Sutton Projects, Termite Economies (Neural Nodes and Root Causes) and Termite Economies (Phase 1) (both 2020) include diagrams of this algorithm layered over 2-D renditions of the first sculpture in the Termite Economies series. This original sculpture was based on the architecture of a quarry, 3-D printed then air brushed with a red-dirt pigment. Mangan has likened the traces of this pigment left behind on the scrap paper beneath the sculpture to the pheromone traces used by termites as behavioural triggers for their co-workers.3

The sculptural object of Neural Nest (slice) itself is a curved, three-dimensional cradle of delicate interconnecting tubes. Again 3D-printed and air-brushed in a copper-like colour, it simultaneously connotes the masticated dirt of termite mounds and the cables used in internet and telephone connections, which were originally modelled on insect swarm logic. This biomorphic, brain-like shape is sawn flat down the front—not unrelated to Paul Thek’s severed wax limbs encased in Perspex boxes from the 1960s. In looking at Neural Nest (slice), I can’t help but recall the nauseating anti-smoking Australian public service announcement on TV in the early 2000s—where gloved hands take the brain of an ex-smoker and clinically cut it in half to reveal internal blood clots; instrumentalising the violence of scientific objectivity to achieve its emotional impact. In Neural Nest (slice), Mangan deliberately chose to remove the frontal lobe—responsible for, amongst other things, mood changes, decision-making and judgement. Deeply informed by Catherine Malabou’s ideas around the addicted brain, this particular sculpture—like the exhibition more broadly—is motivated by the possibility of cultivating new neural addictions and decision-making patterns in humans.4

Indeed, Termite Economies does not simply dwell on and reiterate the ever-widening rift between nature and culture by restaging the violence of the cut: whether through ancient geologic strata or the supple human brain. Characteristic of Mangan’s practice more broadly, Neural Nodes and Root Causes harnesses its speculative qualities to imagine alternate realities: like the biofuel-powered revolution in Progress in Action (2013) or the ancient coral coffee table industry that would save a dying environment and economy in Nauru—Notes from a cretaceous world. By rewiring the human brain to think like a termite, the sculpture imagines a different means of human existence in the world: an existence that is collectivised and intricately entwined with the materiality of place. Indeed, when entomologists write about termite mounds, ant hills and beehives, there is often debate around the precise unit of measurement: that is, whether the ‘individual’ should be defined at the level of the singular termite, ant or bee, or the mound, hill or hive that the insects occupy. There is a sense in which insect architecture itself is a brain and body, a living and breathing organism, and that the colony of insects within are merely its buzzing atoms. As Jussi Parikka writes in Insect Media: An Archaeology of Animals and Technology (2010), in the social life of insects, ‘reason is distributed and always fundamentally intertwined, or afforded by, its collaborations with the world.’5 This conception of the decentralised, collective or ‘hive’ mind cuts across anthropocentric, neoliberal and capitalist prerequisites of human exceptionalism, individuality and, of course, nature–culture separation.

Neural Nodes and Root Causes emerges against the backdrop of climate crisis and is, more specifically, animated by the very real threat of insect extinction.6 The event of insect extinction is predicted to initiate a devastating chain reaction across the world’s ecosystems, spelling catastrophe for the various human and non-human lives sustained by them, and thereby highlighting our/their profound interdependence. In this, the period of the Anthropocene, of human-induced environmental catastrophe, the need to rewire human mentality, to delink from destructive behavioural patterns and think and act in solidarity across species has simultaneously never been more urgent and yet felt less likely.

HELEN HUGHES

Research Fellow, Department of Fine Art, Monash University

May 2020

…

1. Nicholas Mangan, ‘Termite Economies’, lecture, NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore, November 23, 2019.

2. Ibid.

3. The artist has explained this concept in more detail in a recent statement for New Zealand’s Mossman Gallery. He writes:

These airbrush works on paper of mine evolved as a happy accident in the studio while painting the 3D-printed forms that make up the sculptural element in ‘Termite Economies (Phase 2)’, shown at Hopkinson Mossman in 2019. Lifting up the forms after they were sprayed, I discovered a whole other set of possibilities and architectural potentials. This enabled something more haptic within a project that was otherwise highly considered and planned through computer modelling and mechanised production. The drawings evolved by tracing around the forms. Like X-rays or scans, they are suggestive of tracks and traces that termites leave behind as they forage and build their habitats around themselves. They mimic the pheromone or chemical signals that enable communication within their colonies, the spray paint hinting to the chemical-impregnated dirt concentration and dispersion.

The forms left on the page are traces, spectral records of the computer-generated sculptural forms. Produced using software which deployed stigmergic algorithms, the sculptures themselves modelled and coded translations of pheromone or chemical cement trails of termites.

French entomologist Pierre-Paul Grassé coined the term stigmergy in 1959 to describe the organisation mechanism used by insects (the principle is that work performed by an agent leaves a trace in the environment that stimulates the performance of subsequent work—by the same or other agents). Stigmergy as a term is derived from the etymological Greek roots—’stigma’, to leave a ‘mark’ or ‘trace,’ and ‘ergon’, which can mean ‘work, action, or the product of work.’

Entomologists and computer scientists have observed termite behaviour and translated this into computer software for uses such a traffic flow management, viral marketing, and many other social networking we take for granted. I question if we might be witnessing an example of stigmergy being expressed through the current rollout of digital contact tracing apps under Covid19 through Bluetooth ‘Betweenness’.

4. See Catherine Malabou, What Should We Do With Our Brains? (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), particularly ‘Chapter 2: The Crisis in Central Power’, 32–54.

5. Jussi Parikka, Insect Media: An Archaeology of Animals and Technology (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 146.

6. See, for instance, Damien Carrington, ‘Plummeting Insect Numbers Threaten ‘Collapse of Nature’, The Guardian, February 10, 2019.

List of works: