Jon Campbell Gone to see a man about a dog

17 July –14 November 2020

Welcome to the Sutton Gallery Viewing Room.

Please provide your contact information to view the current selection of works.

By sharing your details, you agree to our Privacy Policy and will receive gallery newsletters.

Sutton Gallery Online is pleased to present Gone to see a man about a dog, a new body of work by Jon Campbell featuring individual paintings, alongside a series of works made in collaboration with Stephen Bush. This exhibition forms part of an artist swap held in conjunction with Darren Knight Gallery, who will host an exhibition by Bush later this year.

While access to the gallery is temporarily suspended, here you can browse available works and discover Campbell’s exhibition via a short video walk-through. This online presentation also features a new essay by curator Lisa Sullivan, originally conceived as a print publication to accompany the artist swap. In Gone Dead, Sullivan charts the formation of Campbell and Bush’s friendship alongside the concurrent Melbourne independent music scene. This text reveals how each artists shared connection to music cemented their friendship, moulded their careers, and eventually led to their creative collaboration.

one city on two tongues

buried here in these blankets

all shoulders hips and ankles

washed in television fumes sayin’

“how did we get here so soon?”

[The Moodists, ‘Chevrolet Rise’, 1984]

2020 marks the forty-year friendship of Jon Campbell and Stephen Bush. They met when Jon enrolled in the painting department at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in 1980. Stephen had completed the three-year Bachelor of Arts course in 1978, followed in 1979 by a Graduate Diploma, and in 1980 was a part-time lecturer in the course that Jon travelled from Melbourne’s western suburbs to attend.

Reflecting in 1999 on their meeting, Jon noted that Stephen, and a small number of other lecturers including Geoff Lowe, Jon Cattapan and Peter Ellis, were his ‘biggest influence … in terms of my thinking about becoming an artist.’1 But beyond this early immersion in the art world, it was Melbourne’s thriving independent music scene in which Jon and Stephen’s friendship consolidated in a convergence of art and music that has run through their careers and shaped their professional and personal relationship.

In the early 1980s Jon and Stephen were living in close proximity in St Kilda, then the centre of Melbourne’s post-punk scene. The Crystal Ballroom (subsequently Seaview Ballroom) was ‘the off-campus hangout for inner-city art schools’ including RMIT and the Victorian College of the Arts.2 Similarly, at the other end of Fitzroy Street, the Prince of Wales was a much-loved bar and gigs at both venues were an essential part of Jon and Stephen’s social life and cultural milieu.

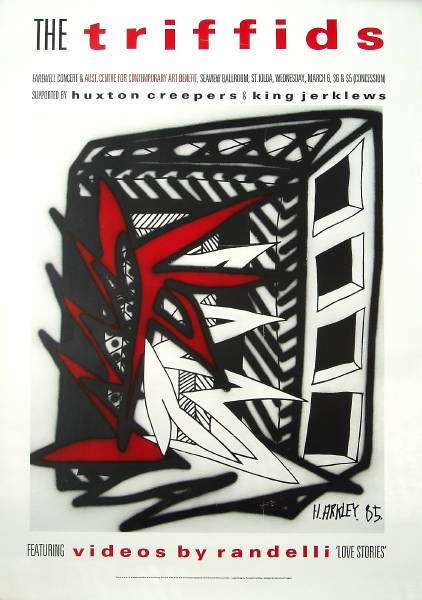

During further studies at the VCA in 1984–85 Jon’s art school band King Jerklews (1984–87) played the Seaview Ballroom and the Prince of Wales. In March 1985 they supported The Triffids in their farewell gig at the Ballroom (along with Huxton Creepers)—a fundraiser for the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, with a promotional poster designed by Howard Arkley, another influential lecturer throughout Jon’s VCA years.

In the decades since, music has been a touchstone for aspects of each artist’s practice—but not just any music, a certain type of music that comes out of an underground scene, that has an energy and rawness about it, a critical edge or a deep emotional resonance. In the early 1980s Jon and Stephen were enmeshed in what was arguably one of the most dynamic periods of live music in Melbourne’s recent history, and it’s the visceral response to the energy of a live performance that they’ve each sought to translate into their paintings over the years: that indefinable thing that summons a ‘fuck yeah’ at the end of a gig.

It’s also about the energy or essence of an artist captured in a recording: the primeval sounds and surreal word associations of Captain Beefheart or the poetic emotion of Nick Drake. The titles of songs by both have been assigned to works by Stephen, not merely as an afterthought, but because his paintings distil the feelings the songs elicit for him.3

Stephen and Jon have also mined their music collections for exhibition titles—from Drake’s Bryter Layter and The Fall’s Open the Boxoctosis to The Saints’ I’m Stranded and the mainstream ‘Top 40’ compilations ‘Explosive Hits’ and ‘Greatest Hits’. This deep engagement has not just been about Jon and Stephen drawing inspiration from music: their works have also been used by musicians to encapsulate the ‘spirit’ of a record, with paintings by each being reproduced on the covers of albums. Stephen’s The Lure of Paris #27 (2007) on New York indie rock band Silver Jews’ Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea (2008) and Jon’s Have a Go on Melbourne band Harem Scarem’s single Rub Me the Right Way (1989). More recently, Jon was commissioned to design the cover art for Sunnyboys 40 (2019) marking the 40th anniversary of the band’s debut release.

Jon has painted and collaged onto record covers, painted band set-lists, and in a 2006 video work he made Bob Dylan’s Subterranean Homesick Blues (1965) his own by replacing Dylan’s politically charged lyrics with his own lexicon including ‘relax’, ‘love’, ‘I’m stranded’, ‘so you wanna be a rock ’n’ roll star’, ‘we wanna be free’, ‘afternoon delight’ and ‘blah blah blah’. He reflected in 2010:

“I guess rock ’n’ roll had the vibe, the feel the looseness that I was thinking about for my art, it did have story telling, it was connected closely to the audience, if you had the desire you could do it, it had a simplicity to its structure, kinda like painting—three chords, guitars, drums, vocals, verse, chorus, paint, brushes, canvas—but became complex in what you did with it, how you made it interesting or different from the next artist. It seemed obvious to make music part of the subject matter, I can’t really describe why; it’s like listening to certain songs, they just move you, you can’t exactly say why ….”4

Jon and Stephen’s early careers aligned closely: exhibiting in institutional group shows together in the ’80s and ’90s, as well as shared commercial representation, with Jon joining Stephen at Melbourne’s Powell Street Gallery in 1987 and after its closure in 1993, both moving across to Robert Lindsay Gallery in Flinders Lane.5 In 1998 and 2002 Jon and Stephen exhibited for the first time with their respective current galleries, Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney, and Sutton Gallery, Melbourne—commercial galleries that have their own aligned histories, with each being established in the Melbourne suburb of Fitzroy in 1992.6

After forty years, the ‘here’ that Jon and Stephen have arrived at is a ‘gallery swap’ with each of them exhibiting at the other’s representative gallery: Jon’s exhibition Gone to see a man about a dog at Sutton Gallery and Stephen’s From the Rubber Room at Darren Knight Gallery. The gallery swap has been the catalyst for a creative collaboration that brings together the artists’ distinct stylistic approaches whilst further reinforcing the characteristics apparent in both of their practices such as repetition and quotation.

****

Heard it, heartache

Your turn, my turn

Show it, your face

Your turn, my turn

[The Go-Betweens, ‘Your Turn, My Turn’, 1981]

This collaborative project has involved the artists exchanging paintings for the other to work with—a selection of recent and earlier canvases and works on paper, at various stages of completion or resolution. In response to the other’s work, they’ve filled empty spaces or overlaid text or figurative imagery onto existing compositions. It’s the first time they’ve collaborated, but in many respects it’s a natural development particularly given Stephen’s work is characterised by unexpected conjunctions (for example, goats, historical figures, beekeepers and mid-century architecture within psychedelic swirling landscapes) and Jon utilises fragments of dialogue drawn from a wide range of sources and inserts these back into everyday life in the form of wall-paintings, neons, flags and banners (words and phrases such as ‘Yeah’, ‘Fuck Yeah’, ‘Insufficient funds’, ‘Absolutely disgusting’, and ‘It’s a world full of cover versions’).

Additionally, Stephen’s inclination to work ‘within a variety of self-imposed and at times, performative frameworks—whether it be painting Babar the Elephant from memory in his ongoing The Lure of Paris series (1992–); working monochromatically with a particular colour (sienna red, green, purple); [or] introducing the use of paint as viscous liquid as a way of embracing chance and the accidental’, finds its natural extension in this game-like exchange with defined parameters.7 In an interview in 2012, Stephen stated:

“I suppose part of my work is inherently struggling against having things ‘fit together’. The interesting moments occur when logic deteriorates and formal barriers erode, thereby creating opportunities for friction and tension to surface.”8

The resulting works play out like conversations between close friends: the voices are distinct and fill the spaces that are open to them. Each artist’s deep knowledge of the other’s work comes from a long-standing friendship—and the trust this engenders—so in these collaborative works there is a special energy rising from their enthusiasm for how the other might ‘riff’ off their painting. The imagery, words, phrases, colour schemes and execution are familiar to us, but the juxtapositions create new and unpredictable narratives and readings. This melding of imagery is a ‘bricolage’—a recasting of separate materials, artifacts and images to produce new meanings and insights—just as bricolage was a term applied to the punk movement (and Melbourne’s independent music scene of the late ’70s and early ’80s).9

In his compendium of writings, The 10 Rules of Rock and Roll, musician Robert Forster wrote of his decades-long friendship with Grant McLennan: a friendship that can be traced back to their first meeting in 1976 in the drama department at the University of Queensland where they were studying Bachelor of Arts degrees. Robert and Grant formed The Go-Betweens in 1978 and collaborated for thirty years. While Jon and Stephen’s creative collaboration is in its infancy by comparison, the parallels between the genesis and longevity of their friendships are clear, and it’s easy to imagine that the sentiments Robert expressed might equally apply, when he described his friend and collaborator as:

“the person you can go to who is so much on your wavelength, stocked with shared experience, whom you don’t ask for life advice … but who, as a fellow artist, you can go toe to toe with and always come away totally inspired by. Well, that’s a great thing.”10

1 ‘Wide-Eyed: Melbourne, the USA and back again: Jon Campbell talks to

Robert Rooney’, Jon Campbell’s Greatest Hits Vol. I, ex. cat., Glen Eira City

Gallery, Melbourne, 1999, p. 7. Cited in Lisa Radford & Jarrod Rawlins,

Jon Campbell, Uplands Publishing, Melbourne, 2010, p. 6.

2 Lisa Dethridge, ‘The Crystal Ballroom’, in Dolores San Miguel, The Ballroom: the Melbourne Punk and Post-Punk Scene, Melbourne Books, 2011, p. 10.

3 Stephen Bush, Sure Nuff Yes I Do, 2004, oil and enamel on linen, Private

collection, San Francisco (after the 1967 song by Captain Beefheart);

Stephen Bush, Brighten My Northern Sky, 2004, oil and enamel on linen,

Private collection, Melbourne (after Nick Drake’s song released in 1971).

4 Radford & Rawlins, op. cit., p. 39.

5 Co-exhibitors in the following exhibitions: Fears and Scruples, University

Gallery, University of Melbourne (1986); Young Australians, National Gallery

Victoria & National tour (1986–88); Domino 1—Collaborations Between

Artists, Ian Potter Gallery, University of Melbourne (1992); Survey 4:

Images of the Geelong Region, Geelong Art Gallery (1993); Tableaux: Works

from the Collection, Monash University Gallery, Melbourne (1994); NON,

ether ohnetitel, Melbourne (1995); If You’re Creative You Can Get Stuffed,

Continental Cafe, Melbourne (1995); The Vizard Foundation Art Collection of

the 1990s, Geelong, Hamilton and Bendigo Art Galleries (1997); Leisure &

Pleasure, Robert Lindsay Gallery (1999); On the Road: the Car in Australian

Art, Heide MOMA (1999–2000). Stephen Bush exhibited at Powell Street

Gallery from 1984–91 and Robert Lindsay Gallery from 1994–99. Jon

Campbell exhibited at Powell Street Gallery from 1987–92 and Robert

Lindsay Gallery from 1995–97.

6 Darren Knight Gallery operated in Smith Street before relocating to

Sydney in 1997, and Sutton Gallery launched in its current location

on Brunswick Street.

7 Kelly Gellatly, Stephen Bush: Steenhuffel. The Vizard Collection Contemporary Artist Project 2014, ex. cat., Ian Potter Museum of Art, The University of

Melbourne, 2014, p. 20.

8 Phaidon, ‘Inside the mind of Stephen Bush’, [8 February 2012], viewed 31

May 2020, https://au.phaidon.com/agenda/art/articles/2012/february/08/

inside-the-mind-of-stephen-bush/

9 Chris McAuliffe, ‘Let’s talk about art: art and punk in Melbourne’, Art and

Australia, vol. 34, no. 4, 1997, pp. 502-12.

10 Robert Forster, The 10 Rules of Rock and Roll: Collected Music Writings /

2005–09, Black Inc., Melbourne, 2010, p. 221.